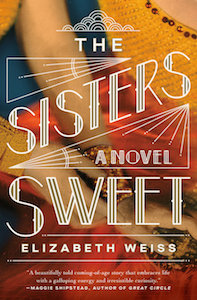

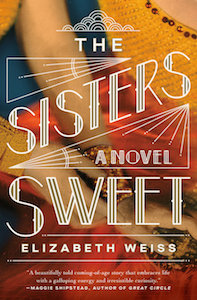

The puppets in my novel, The Sisters Sweet, show up fleetingly. They are a detail in a family history, nothing more. But at the edge of every page flicker the shadows of other puppets only I can see—the midwives and muses who helped drag the book out of me over the course of a decade.

A few of them: an enormous snow-white owl, making her slow flight through the woods beside the Mississippi. A puppet built by my teenaged students at a summer camp, whose execution of a rude anatomical joke still makes me laugh, years later. A strip of fabric the brilliant puppet artist Basil Twist draped over an electric fan angled upward and then brushed with his palm, coaxing its transformation from a flat surface into a living creature, a body filled with breath.

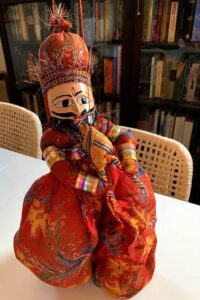

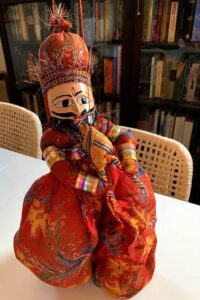

And my own puppets, the home team: Perched on a doorframe, a couple in jewel-toned garments, each controlled by a single string, his running from the tasseled tip of his hat to the reed instrument he holds between his hands, hers connecting what would be her fingertips, if she had fingers. (Years ago, on a street in Jaipur, India, I watched a performer flick a similar pair into a pas de deux.) On top of the tall bookcase, a hand puppet from the Brúðuheimar Center for Puppetry Arts in Iceland, denim-clad, with bright, wide-set eyes that stare out from beneath a white thatch of sheep's wool hair. A toy marionette, a Little Red Riding Hood who sits in my bedroom window, the sight of her—slumped over, face pressed against the glass—unnerving when I glance up from the street.

And my own puppets, the home team: Perched on a doorframe, a couple in jewel-toned garments, each controlled by a single string, his running from the tasseled tip of his hat to the reed instrument he holds between his hands, hers connecting what would be her fingertips, if she had fingers. (Years ago, on a street in Jaipur, India, I watched a performer flick a similar pair into a pas de deux.) On top of the tall bookcase, a hand puppet from the Brúðuheimar Center for Puppetry Arts in Iceland, denim-clad, with bright, wide-set eyes that stare out from beneath a white thatch of sheep's wool hair. A toy marionette, a Little Red Riding Hood who sits in my bedroom window, the sight of her—slumped over, face pressed against the glass—unnerving when I glance up from the street.

I got curious about puppets my first semester of college, when a professor with the perfect puppet-person name of Ansley Valentine gave me a small role in a puppet-heavy theater piece. I didn't actually get to do any puppetry, but every night I watched from the wings, stunned to discover that puppets could be beautiful and strange, something more than children's entertainment. After graduation, I moved to New York, where, weeks after my arrival, I wept at the sight of a mutton-chopped, bug-eyed avatar of Henrik Ibsen, prone and lifeless at the end of the astonishing puppet play The Death of Little Ibsen. I left the theater obsessed.

It was around that time that I started to get serious about writing. In the years since, my puppet life and my writing life have become entwined.

I am an anxious person whose mind tends toward the pragmatic and fretful. For me, writing requires escape: a physical escape, from home to coffee shop or library, and more importantly, an escape from the part of my brain that churns with worry (about the dog's ear medicine and the baby's spaghetti and lead poisoning and every embarrassing thing I've ever said at a party) into the wide-open expanse of my imagination. The place where generating fiction feels possible.

Puppets are my escape hatch.

When I watch a dying puppet dip his head, or a lustful puppet shimmy, or a grieving puppet's shoulders rise and fall with her ragged breath, the precision and overtness of the puppet's movement sharpens my attention. The imaginative act that precedes that movement—the sensitivity and specificity with which someone must have noticed in order to make legible, through the puppet's body, some truth about what it is to be alive, to think, to feel, to move—braces me. In the company of puppets, I grow more receptive to the infinite parallel universes of people's lives, the human experiences that are the stuff of the stories I want to tell.

In his exquisite book, Puppet: An Essay on Uncanny Life, Kenneth Gross describes the distortions of proportion and scale typical of the puppet theater:

"The eyes of a puppet head may expand even as the mouth shrinks or disappears. The hands and feet grow large to match their expressive use, even as a torso disappears to nothing." On a puppet stage, "mice may be the size of elephants, a hand may be as large as a planet."

"The plays of scale in puppet theater are about more than visual paradox," Gross writes. "They suggest that we do not yet know the dimensions and limits of what we call life."

Puppets bend my mind toward the impossible, expose the edge of life as I know it and invite me to look around to the other side. They shock me into dreaming.

Sometimes, that is all I need from puppets: a nudge into the more open, more creative part of my brain. I saw Basil Twist perform with that strip of cloth during a workshop he gave for theater and dance students at the University of Iowa (loosely affiliated to the university through a part-time teaching gig, I had sweet-talked my way in). At the time, I was staring down a deadline to get a draft of my novel to my agent—the last draft, we'd decided. And I couldn't and I couldn't and I couldn't, until I spent three hours on an empty stage with a bunch of actors and dancers and some fabric and cardboard and a genius puppeteer, and at the end of it, something had shaken loose. I went home and wrote in a frenzy, finishing in a matter of weeks

Puppets also turn up for me in the thick of the work of writing—the nitty-gritty, problem-solving stage.

In his essay "The Myths of the Puppet Theater," the puppeteer Eric Bass points out that much of our common language around puppets—"He played him like a puppet. Puppet government"—is rooted in a broken metaphor, a myth about the relationship between puppet and puppeteer.

"As puppeteers, it is, surprisingly, not our job to impose our intent on the puppet," he writes. "It is our job to discover what the puppet can do and what it seems to want to do. It has propensities. We want to find out what they are, and support them. We are, in this sense, less like tyrants, and more like nurses to these objects. How can we help them? They are built for a purpose. They seem to have destinies. We want to help them arrive at those destinies."

A character in a draft of a novel doesn't have the inherent physical properties of a puppet, but at a certain point she has a fully imagined life out of which impulses emerge that can either be supported or ignored. As I revised my novel, I sometimes found myself trying to force characters to act in ways that didn't feel true. In retrospect, I see that I was trying to make them illustrate a theme, or show off some bit of research, or behave more likably. Getting unstuck meant I had to think like a puppeteer, to yield control, to stop trying to make the character act as I wished she would and, instead, to trust her to live out her own story.

Puppets also turn up for me in the thick of the work of writing—the nitty-gritty, problem-solving stage.

A few weeks ago, I took my family to the park near my house for a Dia de los Muertos procession that promised spectacular giant puppets (my neighborhood is known as a hotbed of puppet activity, which is not the reason my partner and I moved here). When we arrived, the park was teeming with stilt-walkers and people grinning out of great, slab-like vegetable masks—a radish, a turnip. A bicycle-mounted carrot whizzed up the path. Three towering Catrina puppets danced in a slow circle while a larger-than-life neon moose stumbled around the basketball court. A human skeleton the height of a small house dangled from a frame, waiting for a team of puppeteers to guide her steps along the street.

A man emerged from the crowd, waving a clipboard.

"We need a puppeteer!" he shouted. "Does anyone want to be a puppeteer?"

My family turned to me, excited.

"Now's your chance," said my sister. "It's what you've been waiting for."

I shook my head. This isn't what I want from puppets. I can't make them with any competence, I can't operate them with any skill. I am strictly an enthusiast. An amateur.

But I think that's exactly why puppets are so good at helping me get out of my own way. Amateurism—from the Latin for "love"—offers a delicious freedom. There is no ambition in my puppet life, there are no stakes. Puppets always feel to me like writing does on the best days—as uninhibited and ecstatic as childhood play.

When I got home from the park that afternoon, for the first time in weeks, the new novel I am working on felt alive in my mind. I wrote.

I think every writer needs something that affects their brain in this way: a circuit breaker, a reset. Maybe for some it's tennis or meditation or painting or making pie. When I find myself impeded by my desire to succeed, by the demands of daily life, by the weight of words, puppets propel me somewhere free and wild. They teach me to play my way back to the page.

__________________________________

The Sisters Sweet is available from The Dial Press. Copyright © 2021 by Elizabeth Weiss.

And my own puppets, the home team: Perched on a doorframe, a couple in jewel-toned garments, each controlled by a single string, his running from the tasseled tip of his hat to the reed instrument he holds between his hands, hers connecting what would be her fingertips, if she had fingers. (Years ago, on a street in Jaipur, India, I watched a performer flick a similar pair into a pas de deux.) On top of the tall bookcase, a hand puppet from the Brúðuheimar Center for Puppetry Arts in Iceland, denim-clad, with bright, wide-set eyes that stare out from beneath a white thatch of sheep's wool hair. A toy marionette, a Little Red Riding Hood who sits in my bedroom window, the sight of her—slumped over, face pressed against the glass—unnerving when I glance up from the street.

And my own puppets, the home team: Perched on a doorframe, a couple in jewel-toned garments, each controlled by a single string, his running from the tasseled tip of his hat to the reed instrument he holds between his hands, hers connecting what would be her fingertips, if she had fingers. (Years ago, on a street in Jaipur, India, I watched a performer flick a similar pair into a pas de deux.) On top of the tall bookcase, a hand puppet from the Brúðuheimar Center for Puppetry Arts in Iceland, denim-clad, with bright, wide-set eyes that stare out from beneath a white thatch of sheep's wool hair. A toy marionette, a Little Red Riding Hood who sits in my bedroom window, the sight of her—slumped over, face pressed against the glass—unnerving when I glance up from the street.

No comments:

Post a Comment