Over 120 years since the Victorian era ended, its literature continues to have huge staying power in the collective imagination of the English-speaking world. We all have a clear idea of what "Dickensian" London looks like. We know what it means to be a Scrooge, or to be a bit Jekyll and Hyde. Most of us know the twist in Jane Eyre and what happens in Tess of the D'Urbervilles before we ever pick up the novels. We study Victorian books at school and university, adapt them for screen, write retellings. Just look at all the twenty-first-century reimaginings of the Sherlock Holmes stories: the films with Robert Downy Jr., BBC's Sherlock, Elementary, Enola Holmes, and so many more.

There are particular cultural and social reasons—often not good ones—why a book might become a "classic" in the first place, while other books by other authors or from other times and places get forgotten. It's impossible to separate the legacy of the Victorian period and its literature from the huge political and social power Britain exercised through its Empire and its concerted attacks on other cultures, both during the Victorian period and before and after.

When it comes to Victorian books themselves, some are easier to separate from this than others; you can't read any Rudyard Kipling or much Arthur Conan Doyle without encountering imperialist and racist views; but for other Victorian authors, the Empire was something that influenced their world but that they rarely wrote about. Regardless, Victorian literature would certainly not be so widely read today were English not so widely spoken as a language, and that too is a legacy of imperialism.

However, while this goes some of the way to explaining why many Victorian books have become "canon," it doesn't really explain why we still love these books. And the fact is that a lot of us do. On my YouTube channel, Books and Things, I run the readathon Victober with a few fellow BookTubers. We dedicate the month of October each year to reading Victorian literature. It's been running for over six years, and we now have thousands of enthusiastic participants from all over the world.

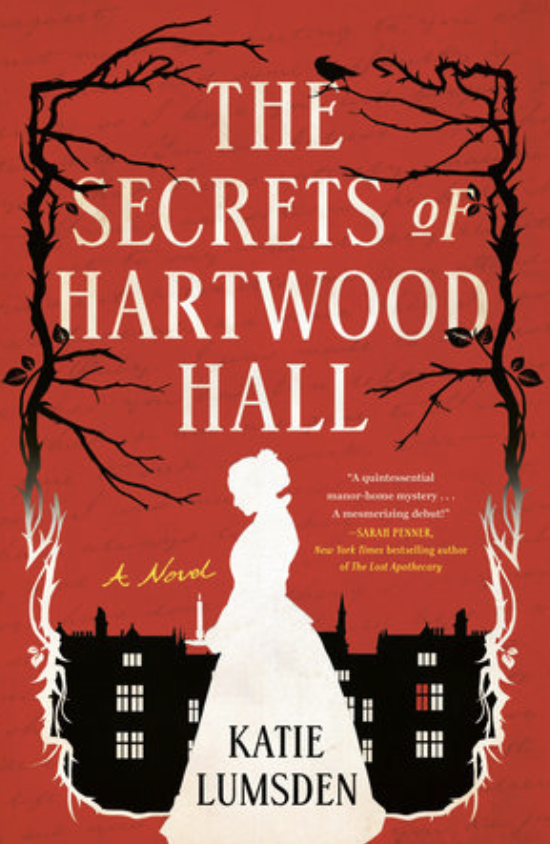

I have loved Victorian literature since I read Jane Eyre aged thirteen. These days, I've run out of Victorian books to read that are still in print, so I read out-of-print, forgotten books—very old editions, or digital versions I've tracked down. I read and love a lot of contemporary literature, too, and I love reading books from throughout history, from around the world; but when writing my debut novel, The Secrets of Hartwood Hall, I found myself drawn again to the Victorians.

The peculiar technological and social circumstances of Victorian Britain gave writers the chance to redefine the novel.

The book is set in 1852 and follows Margaret Lennox, a twenty-nine-year-old governess, returning to work after the death of her husband. She takes up a new position at Hartwood Hall, an isolated country house, where things are not quite what they seem. The novel is a love letter to my favorite books.

Of course, the Victorians didn't just happen to write lots of amazing books. There is a specific context that led to the creation of their literature, and certain features that have given it its staying power.

At the start of the Victorian period, the novel was a relatively new form. The first novel in English is usually said to be Robinson Crusoe, published 118 years before Queen Victoria ascended to the throne; but in its first century, the novel was often not taken seriously. It was felt that serious people read non-fiction and poetry, while novels were frivolous: guilty pleasures that might even have detrimental effects on the moral character.

The peculiar technological and social circumstances of Victorian Britain gave writers the chance to redefine the novel. Improvements in printing technology meant that books, newspapers and periodicals were quicker and cheaper to produce, easier to buy. The publishing industry expanded—indeed, it became an industry—and grew more commercialized, making writing into a viable profession. Novels were serialized in journals, and everyone waited eagerly for the next installment.

Literacy rates increased dramatically in Victorian Britain, partly due to the growth of the middle classes, partly due to education acts making schooling more widely available. Parliamentary acts also cut down working hours in factories, and technological changes shortened the length of tasks both in and out of the home—which meant that, as the era went on, at least some Victorians had increasing amounts of leisure time.

All this gave novelists new audiences and new opportunities—and, with growing competition, more reason to experiment and try new things. This great hunger for literature is partly why Victorian authors were so prolific. Anthony Trollope wrote forty-seven novels; Mary Elizabeth Braddon wrote over eighty; Margaret Oliphant, now somewhat forgotten but hugely successful in her day, wrote nearly 100.

The new prominence of the novel also transformed how it was viewed. While some fiction continued to be looked down upon—such as the cheap, sensational "Penny Dreadfuls"—many novels became respectable. Novels grew to be perhaps the first form of mass entertainment, popular throughout a variety of social groups. People from all classes and walks of life enjoyed Charles Dickens, for example. Dickens is often considered to be the first real celebrity; he toured the UK and the USA extensively, reading extracts of his work live to massive audiences. In The Warden, Anthony Trollope created a satirical version of Dickens called "Mr. Popular Sentiment," and the implication is clear: that Dickens was felt to speak for—and, indeed, shape the opinion of—the majority.

Novels could even be important tools for social criticism. Frances Trollope's Michael Armstrong, The Factory Boy was written with the aim of exposing poor working conditions within textile mills, and its popularity played an important part in pressuring Parliament to pass the Factory Acts of the 1840s. Novels, and their authors, came to be taken seriously in a way they simply had not been before. One novelist, Benjamin Disraeli, even went on to become the Prime Minister.

The change in the novel's status during the Victorian period, alongside the increasing variety and volume of novels, also gave birth to a lot of our modern genres and literary traditions. We all know that Sherlock Holmes gave us the modern detective, but Arthur Conan Doyle was also building on earlier Victorian detective figures like Sergeant Cuff from Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone and Mr Bucket from Charles Dickens' Bleak House.

Sensation novels—books like Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret, Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White and Ellen Wood's East Lynne—blended domestic drama with pacy plots, family mysteries, secrets, and betrayals, bringing crime and deceit into the domestic sphere; in other words, they are the precursors to modern thrillers.

The era also gave us the beginnings of children's literature, science fiction, and horror. Victorian love stories, coming-of-age tales, and gothic works still appeal to us because they have the features we expect. One issue with reading Victorian books today is that they can sometimes appear clichéd—but this is often because they contain the seeds of what went on to become genre tropes.

The Victorian era is when modern English literature as we know it began.

It is not only Victorian genres that feel familiar to us: they also wrote about a lot of themes that still interest and concern us in the modern world. We think of the Victorians as patriarchal, hierarchical, imperialist, and narrow-minded, and it's unquestionably true that these things can be found in their literature in abundance—again, there's Rudyard Kipling—but we can also find passionate arguments against the social status quo.

Elizabeth Gaskell and George Gissing fought against prejudice and class boundaries in their books North and South and The Nether World. Anthony Trollope and Charles Dickens's criticisms of money, excess and corruption in books like The Way We Live Now and Our Mutual Friend still feel pertinent. The Moonstone feels problematic in places, but Wilkie Collins was trying to write an anti-imperialist novel, within the limitations of his time. Victorian literature can be surprisingly proto-feminist, too: books like Margaret Oliphant's Hester, George Gissing's The Odd Women, and Amy Dillwyn's Jill all challenged gender roles and social rules. Jude the Obscure was so radical in its condemnation of class and marriage as oppressive institutions that the response to it effectively ended Thomas Hardy's career as a novel-writer.

The Victorians were also, like us, concerned about technology and its impacts. We often talk about the Victorian period as a homogenous era, but it was, in fact, sixty-four years of huge change. Like us, they lived in a time when technology was rapidly altering the world around them; they, like us, didn't always know what to make of this. They worried about technological development taking away people's jobs; they worried about pollution; they worried about whether technology would change society for the better or for the worse. In his novel Hard Times, Dickens explored technological and industrial change, and how these things were affecting social interaction and the way people thought. Dickens's concern that technology was taking away people's imagination and sense of joy does not feel far away from modern conversations about how the internet and social media affect how we think and interact.

The reason why the Victorian period still interests so many modern readers is because it is long ago but not too long ago. We find their world fascinating but recognizable enough to understand. We keep returning to the works of the Victorians because they wrote great novels, because they wrote so many of them, because they explored themes that still interest us today, because many of our foundational texts come from them. In short, the Victorian era is when modern English literature as we know it began.

________________________________

Katie Lumsden's The Secrets of Hartwood Hall is available now from Dutton.

No comments:

Post a Comment