In 1839, if you were a New Yorker who read newspapers at all, you were acquainted with Madame Restell, as her ads were running continuously in the New York Daily Herald. They were so numerous that, in response to a Dr. Carpenter canceling his advertising, as he did not feel he was being respectfully served, the editor jokingly responded, "To lose Doctor Carpenter, under the circumstances, is to lose one's best and oldest, kindest friend. In my heart I estimate him as much—no, not as much—but very nearly as much as I do that pretty Madame Restell, female physician to the human race, for improving the offspring by limiting their number, and bettering the breed, office at 160 Greenwich Street."

This address, to which she'd moved earlier that year, was already a step up from Madame Restell's original office. Her new workplace was outfitted in such a way as to inspire her customers' confidence in her medical expertise. The lighting was subdued, and the walls were decorated with "anatomical plates, specimens of anatomy ... and other curious and instructive illustrations of her particular doctrine."

Visiting a doctor's office adorned with "specimens of anatomy"—perhaps a skeleton in the waiting room—might strike some as unnerving, but such items were doubtless helpful in explaining her methods. The average person's anatomical knowledge at the time would have been extremely limited and having visuals on hand to illustrate her approach would be useful. Madame Restell also had staff.

The door to her office was said to be manned by an elderly woman, to whom patients stated their case before being introduced to Madame Restell. This may have served as an early screening system, though it would be years before Madame Restell was beset by blackmailers or undercover journalists. Right now, her industry was only beginning to expand.

Even in the short term, 160 Greenwich Street would not be her only business address. Restell's advertisements bragged that she sold over 2,000 boxes of pills in New York City in only five months. This was probably somewhat exaggerated, but she was undeniably having a great deal of success.

Sensing growth opportunities, she expanded to Philadelphia, where she opened a satellite office at 39 South Eighth Street. She explained to the citizens of Philadelphia that she had done so "in consequence to the great demand for her medicines in this city, and the great inconvenience, as well as expense of sending for them from New York."

By age 29, Madame Restell was well on her way to creating an empire. But it was one that required more than pills alone.

Madame Restell may have been very good at her pharmaceutics, but her pills were not infallible, and she was known to be performing surgical abortions as well. One patient in need of a surgical abortion would be the same woman who said she had miscarried five times after taking Restell's pills. Madame Restell informed her, "I can probe you, but I must have my price for the operation."

The patient asked what she would use for this probe, and Restell replied, "A piece of whalebone."

The woman elected to probe herself with whalebone rather than paying Restell for the operation. This was a poor decision on her part; afterward, she had to have a hysterectomy.

There is little evidence of Restell losing patients. Which begs the question—how did she learn to perform such a complex operation so effectively?

The notion of using a sharpened whalebone to cause an abortion is eerily reminiscent of the way coat hangers have been employed to a similar end. Indeed, a whalebone might also come from a woman's closet and achieve the same shape if she were to pull one from her corset and sharpen it.

The procedure would likely be much the same with either device. The whalebone would have to be inserted through the cervical os (the opening to the uterus). Doing so would require a remarkably steady hand, as well as knowledge of the appropriate amount of force to use. Even the smallest error could perforate the bowels (which can kill a woman) or the uterine artery (which can also kill a woman). If the procedure was a success, this wouldn't happen, and the woman would miscarry in two or three days. Yet, even then, she ran the risk of becoming septic, and dying as a result of the infection.

Again, what is truly extraordinary here is that, despite extensive investigations into Restell's practice later on, as well as an eagerness on behalf of the public to track down the names of women who died at her hands, there is little evidence of Restell losing patients. Which begs the question—how did she learn to perform such a complex operation so effectively?

Restell's public résumé alleged that she had learned from French relatives. Newspapers would go on to parrot this, with a New York Daily Herald piece (surprisingly, not in one of her own advertisements) declaring that "her [Restell's] Grandmother was an eminent female physician in Paris, and she has studied the science under the first medical minds, both male and female, of France." It is a very glamorous story.

This would have been comforting to many people, not simply because French people seem sexy and sophisticated, but also because France was thought to be on the forefront of surgical innovation. While American doctors flocked to different cities in Europe throughout the nineteenth century to gain knowledge of medical techniques, the period from 1820 to 1860 was known as the "Paris Period" because of the medical innovation that occurred there.

Within the City of Lights, doctors could follow Parisian physicians through free clinics, watch various operations, and attend lectures on medical subjects at renowned institutions, including the Sorbonne. American schools, by comparison, lacked the large hospitals with hundreds of patients where doctors could gain firsthand knowledge. Most American medical schools through the 1840s did not even require their students to go to hospitals, and only about half required students to dissect a human cadaver.

If Madame Restell had studied in France, as she claimed, it would connote a level of knowledge about the body and its functions that many of her American peers lacked.

Regrettably, this claim was a lie.

What we do know is that Madame Restell—or Ann Lohman—was a British immigrant who had worked as a servant and seamstress prior to her career as an abortionist. For her assertion about being trained in surgical and abortive arts by a French grandmother to be true, there would have to be unaccounted-for years in Restell's life story. Much though she might have wished, she simply did not have time to train in France and learn medical arts. She was extremely busy taking in people's laundry and trying to keep herself and her young child alive on New York's Lower East Side.

But surely, she learned how to perform abortions from someone. Restell was certainly well read—and took immense pride in reading a great deal—but she wasn't someone who taught herself skills from books. In the case of her work as a seamstress, she learned from her first husband, a tailor, and then quickly exceeded his skills in the arena. The same can be said of learning to make pills from the pill compounder who lived near her. She surpassed her mentors routinely, but she did typically have a mentor.

As for such a medical mentor, there are a few possibilities.

First, it's hard to overstate how unglamorous surgery was during the early 1800s. In 1796, it was stated by Lord Edward Thurlow in the British Parliament that "there is no more science in surgery than in butchering." This comment prompted one surgeon, a Mr. John Gunning, to reply, "Then I heartily pray your lordship may break your leg and have only a butcher to set it." As sassy as this response may have been, Thurlow wasn't entirely wrong. That's because surgery, prior to the invention of anesthetic in 1846, was a positively terrifying process. Up to 50 percent of patients undergoing surgery died during their procedure—which is one reason hospitals made them pay in advance. Patients knew they might leave with fewer body parts than they'd had upon entering. Even Robert Liston, considered one of the finest surgeons of the period, once accidentally sliced off a patient's testicle in addition to the leg he was amputating.

Depending on how much the butcher liked to demonstrate his methods to his employees, it's possible that she had a very vague understanding of anatomical composition.

Surgery was rarely performed unless the patient seemed likely to die anyway, although some changed their minds when they saw the operating room. Patients would be bound with leather straps to a blood-soaked table, and, as anesthesia did not exist, they would watch while surgeons employed a saw on their extremities.

This was so terrifying that in one instance a patient Liston was about to treat for a bladder stone leapt off the table and locked himself in the lavatory. As Dr. Lindsey Fitzharris wrote in The Butchering Art, "Liston, hot on his heels, broke the door down and dragged the screaming patient back to the operating room. There, he bound the man fast before passing a curved metal tube up the patient's penis and into the bladder." Needless to say, surgeons were not held in the high regard they are today.

In fact, prior to the educational reforms that began in 1815, surgeons were not even considered respected members of the medical establishment. Fitzharris noted that "many surgeons . . . didn't attend university. Some were even illiterate."

In her youth, Madame Restell had worked for a butcher. Doing so meant seeing the cadavers of animals, if not humans. Depending on how much the butcher liked to demonstrate his methods to his employees, it's possible that she had a very vague understanding of anatomical composition. Again, considering that some of her fellow surgeons had no dissection experience at all, this background would have stood her in good stead.

Of course, animal cadavers are not human ones. Any attempts to educate yourself about body composition from them would be a process filled with errors, but it's a technique that has been used before. Galen, the well-known physician and surgeon of the Roman Empire, based his study of human anatomy entirely on animal corpses. This led to some serious missteps—for instance, he believed the female uterus was divided into numerous chambers and looked something like a dog's.

Still, if Madame Restell were literate and versed in a bit of anatomy, she might have been almost on par with some of her less esteemed peers. However, as far as actually performing abortions, her notable success rate would imply a method of trial and error that should have left more of her patients dead or injured than is generally thought to be the case.

What is most likely is that Dr. Evans, the man who taught Restell the art of compounding pills, was doing more than just serving as an apothecary. Fitzharris remarked that "a man who had been apprenticed to a surgeon might also act as an apothecary. ... [T]he surgeon apothecary was a doctor of first resort for the poor." This was probably the case with Evans. His advertisements declared that his "knowledge of medical and surgical practice has been derived from the best schools in England and Scotland."

While the notion that he attended the best schools may have been the kind of exaggeration he was prone to, the claim that he possessed serious surgical skills was probably not. In fact, the same advertisement noted that some of his patients visited him because of "the deviations of the infatuated from morality." It's reasonable to assume he performed surgical abortions.

If Madame Restell became more popular than her mentor, it may have been primarily because she was absolutely more public about the services she provided. It also seems entirely possible that women were more comfortable seeing another woman about their birth control needs than a man. Or perhaps she was just more skilled and innately possessed of a steadier hand than Dr. Evans.

Ultimately, Madame Restell offered her female patients medications and treatments that were as effective as anything the age had to offer. More importantly, she was providing them without any sense of shame or secrecy. For women in need of her services, that made her simply irresistible.

_________________________________

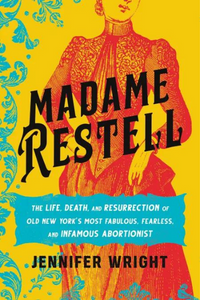

Excerpted from Madame Restell by Jennifer Wright. Copyright © 2023. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment