I'm not sure when it started. This compulsory habit of mine wherein I introduced myself to others, mostly other journalists and later publishing executives with the details of where I grew up: East Texas. Longview, to be exact. It's about 45 minutes west of Louisiana I'd say, and two hours east of Dallas–the closest Texas city. I'd take them through a brief but spiraling explanation of my origins and mostly they'd listen before admitting they still had no idea where it was. And who could blame them?

My hometown is small though increasingly expanding its reach with a rush of new residents pushing into Texas from the coasts. But if you were looking at a map we'd be difficult to find. It's a dot of a town cradled inside a lush stretch of densely populated pine trees that creates the illusion of a never ending spring, surrounded by Caddo lake. Sometimes it feels like a secret we're here at all. Other times it has felt suffocatingly tiny. Perhaps that's why I've been so insistent on people understanding just where I've come from to arrive at the spaces I've often found myself. Maybe it's my way of making sense of the dizzying reality of being both proud of this fact while absolutely terrified that I've never quite belonged.

I was the kinda small town kid that was anxious to leave home, and once I turned eighteen that's what I did. I emotionally managed my formative years escaping into books and late nights dancing by the light of my kitchen stove, imagining a future life outside the walls of home. Because you see, for all its beauty, East Texas has a brutal history and its effects still linger. Much of the state's enslavement of Black Americans happened here. Vast cotton plantations once populated the region, where slaves were trafficked and sold through Mississippi and down Louisiana's Red River then finally across the Texas border.

During the Red Summer of 1919, two years before Tulsa's Black Wall Street was destroyed by white supremacists and its residents massacred, race riots in Longview resulted in a Black man being lynched and Black property ruined. School integration didn't occur until the 70s. Racial abuse was common for me growing up and healthcare afforded to Black residents exceptionally poor in quality.

Because you see, for all its beauty, East Texas has a brutal history and its effects still linger.

So I tucked away my southern drawl and set sail out into the world armed only with a dream that had largely been shaped by television images that promoted a world seemingly far more sophisticated and progressive than anything I'd ever known. Some of that proved true and a lot of it didn't. But it would take me over a decade to realize this and even longer to accept that my mother's words before my departure had been true: People are the same wherever you go.

When I started writing fiction I began with that premise. People. Voices. Experiences. I was initially interested in exploring our similarities. My life as a journalist had provided exposure to so much that was foreign on its surface. For years I hopped around from one newsroom to the next along the eastern seaboard before fully dedicating myself to creative writing. And yet when I sat down to write. To ruminate on histories. To conjure voices and sketch characters, it was a very specific experience that I found my heart chasing on the page. Home.

I eventually returned home in my 30s, newly single, not yet married and without children, prepared to write a book. And despite any accomplishments, to some I was already a failure based on this alone. Writing fiction was an abstract idea to my family and the community I'd left as a teen was equally curious when they saw me again at the grocery store or the bank in town. They unabashedly asked questions like, where you been? Why you back? What you doin now?

For the longest, I wasn't comfortable telling the truth. That I was back because in the end I missed my voice, that sing songy drawl I'd suppressed and saved only for those few I'd allowed closest to me over the years. That I found comfort in the sacredness of the pine and enjoyed feeling invisible inside our little forest. That people were indeed the same everywhere, but East Texas and its people were special to me after all and I wanted to seize every bit of it in my stories.

People were indeed the same everywhere, but East Texas and its people were special to me after all and I wanted to seize every bit of it in my stories.

I was scared to say, I'm a writer. I am writing about yall. This is the only place I can do it.

The transition was rough. I moved back into my childhood room and wrote my novel by hand in narrow-lined notebooks like those I'd used in high school with no idea of whether it would prove worthy of publication. I replaced items my mother had preserved in my absence with new artifacts: I hung Buddhist masks upon white walls and luminous posters of Zora Neale Hurston and James Baldwin. I lit candles and incense. I polished a ceramic Nefertiti and placed her bust beside my bed then diligently unpacked all my books, replacing Ramona Quimby with Gwendolyn Brooks.

I went through long periods of grieving how much life had changed while I was away. My mother was older. I saw her features had changed in ways my annual visits hadn't forced me to absorb. She once caught me rapt in observing the gray in her hair, the small creases beside her mouth and asked, I look old to you? No, it's just been a long time, I said. And this was true in all regards. Cousins I'd once held in my arms as babies were now starting their own families. Church members who'd washed and permed my hair as a girl had passed, or were in nursing homes.

I poured it all into my work. Everything missed. Everyone lost. I took an old tape recorder from my high school days when journalism was the method I thought I'd utilize to tell stories and started capturing their voices. I didn't want to miss a detail, or expression. I wanted to celebrate them while here, and over time, slowly, subtly, it crept into my skin, this remembering and resolution that I was actually happy to be here. At home. Again.

I don't think my family truly understands what I've been doing all these years. Sequestered away writing late nights and dancing outside beneath the stars because now the kitchen feels too small for my imagination. My body. My soul. They don't know how much it pleases me to move in the dark under the streetlight with only the pine as my audience and the occasional nosy neighbor who finds me odd. A foreigner now who went out into the world and returned.

They don't know how much joy I find when I step outside and breathe, exhale and know this is where I belong. In this quiet. In this beautiful, strange place I call E.T. No one will ever truly know the peace I've found, except perhaps my mother when I catch her looking at me and she simply says, I told you so. And I laugh and laugh and laugh because she's right.

_________________________

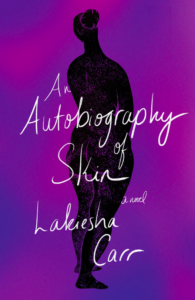

Lakiesha Carr's An Autobiography of Skin is available now from Pantheon.

No comments:

Post a Comment