It's been 18 years since Storming Caesars Palace was first published, and the national mood on matters of race, gender, and economic justice has shifted dramatically. The year 2005 was a low point for social justice activists. George W. Bush's presidency was unfolding in the shadow of the September 11 attacks. The USA Patriot Act, passed by Congress in response, sharply proscribed Americans' civil liberties.

Weeks of protests by 15 million people world-wide had failed to stop the disastrous US military incursions into Iraq and Afghanistan. And in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina's devastation of poor Gulf Coast communities of color, President Bush attempted to eliminate block grants for the Community Development program, a lifeline for low-income communities since the 1960s.

In that grim political environment, the story of a vibrant antipoverty movement organized and led by poor black migrant mothers in Las Vegas, Nevada—was a ray of light and inspiration. But, to many, it also seemed a distant history, vivid echoes of a time of mass protest that had ended long ago. In the early twenty-first century, the now-elderly women activists whose would laugh sadly when young people stopped them on the streets of Las Vegas and asked: "When are you going to come organize us again?" "It has to be your turn now," they would reply.

That time now seems to have arrived. The winds of political change are again blowing. Organizing is happening across the country, jump-started and turbocharged by four years of a neofascist con man in the White House. And women of color have been at the center of this new era of grass-roots uprisings.

Before well-paid white women in media and film began to call out sexual abuse and violence in their workplaces, hotel maids, McDonalds workers, and garment workers were mounting sustained campaigns against sexual violence.

In 2008, the US elected its first African American president—on the strength of turnout among people of color. Three years later, the Occupy Wall Street movement spread from New York to cities across the country and around the world, highlighting the obscene skew of wealth wrought by three decades of neoliberalism. We are the 99%, they chanted: students crushed by debt, families fleeced by medical bills that had cost them their homes, working people of color laboring for wages insufficient to sustain life, unhoused people of all shades who had lost their homes as the debt crisis deepened.

In 2012, low-wage workers at McDonalds and Walmart (mostly women of color) announced the end of their patience after decades of stagnant wages. They began to march and block traffic. They hunger-struck. They showed up uninvited at shareholder meetings and insisted on telling their stories. The nation's poorest workers were invisible no more. That year, they had won for working people raises equivalent to 12 times what Congress had awarded them when it last raised the minimum wage, in 2007.

Throughout the 2010s, women of color organized and marched, leading mass protests and civil disobedience actions with Fight for $15, Black Lives Matter, and the #MeToo movement. Before well-paid white women in media and film began to call out sexual abuse and violence in their workplaces, hotel maids, McDonalds workers, and garment workers were mounting sustained campaigns against sexual violence. The slogan of hotel housekeepers—"Hands Off, Pants On"—became the basis for municipal legislation and union contracts that, for the first time, prioritized women workers' right to be safe from unwanted sexual attention on the job.

And young people of color were everywhere among the millions who mobilized during the 2016 and 2020 Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns: in Chicago, L.A., Queens, the Bronx, and Las Vegas, where hotel maids and cocktail waitresses came out in force for democratic socialism. On the strength of that movement, young people of color were elected to Congress, quickly constituting the strongest support on Capitol Hill for reweaving and strengthening this country's social safety net.

This upwelling of mass activism has thrust the ideas of democratic socialism to the center of American political discourse for the first time in nearly a century, opening up possibilities for a new era of activist government.

Demands for change have been rising up for years: from the streets, from food coops and childcare centers, big box stores, and McDonald's. Young people are tapping the social justice streams of their religious faiths, blocking immigration raids, marching for trans lives and reproductive rights. They've been joined by older activists, including members of Congress who have been getting arrested to preserve voting rights for all. The kind of transformative participatory democracy practiced by Las Vegas mother activists in the 1970s seems once again to be alive and growing.

In the summer of 2020, after the police murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, millions of Americans of every race and age took to the streets to demand change. As in the Occupy movement, they marched not for one day or a few weeks but for months.

That summer saw the biggest racial justice uprisings since the civil rights movements of the 1950s and '60s. Watching, marching, feeling the power of the moment, I felt echoes of the 1970s, when the women activists of the Clark County Welfare Rights Organization and Operation Life were themselves in the streets—fighting for food and housing and education, not just for their children but for all children.

But this was more than a flash on the desert sand. The Strip marches marked the beginning of a years-long campaign of civil disobedience.

It's been a half century since Ruby Duncan, Mary Wesley, Rosie Seals, Essie Henderson, Emma Stampley, and Alversa Beals, their kids and allies—shut down gambling on the famed Las Vegas Strip to protest deep cuts in aid to poor Nevada families. The marchers were there to protest Nevada's decision to cut off benefits to a third of the state's welfare recipients and to slash the benefits of another third. Living on cornmeal and beans for months, Nevada's poor had reached their limit.

On March 6th and 13th, 1971, thousands marched down that desert highway and stormed the gaudiest icon of conspicuous consumption for that time, Caesars Palace hotel and casino. Hotel maids, domestic workers, and cocktail waitresses laughed with pleasure as their kids beat the Las Vegas heat by play- ing in the Caesars' fountains. Famous allies attracted the cameras—film stars Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, feminist icon Gloria Steinem, world-famous baby doctor Benjamin Spock, civil rights leaders Ralph Abernathy and Cesar Chavez. They had joined the march to ensure that no casino mobster or right-wing cowboy acted on an impulse to shoot into the crowd.

But this was more than a flash on the desert sand. The Strip marches marked the beginning of a years-long campaign of civil disobedience in the name of poor children.

These mothers and their children staged eat-ins at Strip hotels, where all-you-can-eat buffets bustled with tourists just blocks from the Westside, where children were going hungry. They held read-ins in white neighborhoods after the Las Vegas library district refused to open brick and mortar libraries in black neighborhoods.

They marched on the governor's mansion, barging in on him while he swam his daily laps to ask if he really didn't have enough money to feed their children. And they sang civil rights songs outside the home of the Las Vegas welfare director at dawn. "Hope you are enjoying your breakfast while our children have nothing to eat," they chanted.

After state officials criticized their protests and insisted that the women learn to work "the system," they did just that for the next twenty years. At the center of an interracial beloved community, "welfare moms" and their kids—aided by attorneys, preachers, and League of Women Voters and Democratic Party activists—applied for and won a dazzling array of federal grants. These enabled them to open and run the Westside's first health clinic, library, public swimming pool, senior citizen housing project, job training center, and much more.

The Operation Life Community Health Center not only offered health care and food but also provided jobs for poor women and their kids. The clinic screened and treated children who had never seen a dentist or an eye doctor, pregnant and nursing women and their babies, and veterans who had been exposed to radiation from the nuclear weapon tests that the U.S. government conducted near Las Vegas until the early 1960s.

Operation Life's motto was "Of the poverty community, by the poverty community, for the poverty community." It served a higher percentage of eligible poor children than any federally funded pediatric clinic in the nation. When asked by officials in Washington, D.C., how they did it, the women replied: "That's easy. We care about the kids."

When first opened, the Operation Life clinic operated out of an old segregation-era hotel called the Cove, once owned by former heavyweight champion Joe Louis and singer-dancer Sammy Davis Jr., among others. The Cove closed after the Strip was integrated in 1965. In 1972, the women, their children, and friends rehabbed the now-crumbling building with their own hands, using scavenged and donated materials and the construction know- how of people in the neighborhood. Sweat equity. When the clinic was opened in the old hotel, some of the exam rooms still had the original wood paneling on the walls and a life-size cardboard cutout of Sammy Davis Jr. in the waiting room.

The women also repaired the Cove swimming pool and reopened it for the neighborhood children during summers, when temperatures routinely hit 115 degrees. Operation Life applied for and received federal funding to provide free meals, feeding upwards of ten thousand children.

In a community where homes were small and crowded, children needed a clean, well-lighted place to study and books that fed a healthy sense of self. Well before the University of Nevada began to offer courses in African American studies, the Operation Life women raised enough money to amass the largest collection of African and African American studies books in Nevada. These books became the core of the first library on the Westside. (In the twenty-first century, the district built a new Westside library, with a performance space; practice rooms for dancers, singers, and actors; a homework help room; and a 3D printer.)

Operation Life became a job-creation engine in a community where underemployment has been a perennial problem. As mothers, the founders of Operation Life understood that decent affordable daycare was essential if women were going to pull themselves out of poverty. So, they won grants to train women as early childhood education providers. They opened a daycare center to provide jobs to neighborhood women and helped many others find jobs in early childhood centers around the city. They also hired local high school and college students to report and write for a community newspaper.

Operation Life also launched a program to provide free solar panels to the city's poor. This was, to the women, a no-brainer in a city where the hot desert sun beat down almost every day of the year.

By the late 1970s, Operation Life employed over one hundred people and offered entrepreneurship training and federal loans for poor women who wanted to open their own businesses. A few of these black-woman-run businesses continued into the twenty-first century.

Operation Life also launched a program to provide free solar panels to the city's poor. This was, to the women, a no-brainer in a city where the hot desert sun beat down almost every day of the year. In our age of catastrophic climate change, that move—like so many others made by Operation Life's founding mothers—is worth revisiting.

The women felt that all of their programs—education, job training and creation, parenting classes, even the swimming pool—were intended to lower crime rates in the area. But in the surge of violence that accompanied the crack epidemic of the 1980s, Westside families were increasingly worried for their safety. So, Operation Life won grants from the federal government to distribute cutting-edge locks and alarms. Anything to improve the lives of poor families.

The twenty-first-century rallying cry "Black Lives Matter" is an apt continuation of the movement, led by poor, black, single migrant mothers from Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Texas who migrated to Las Vegas in the 1950s and '60s seeking a better life for their children. There they faced off against welfare bureaucrats, mob-affiliated hotel/casino owners, and conservative politicians to insist on their rights as human beings, workers, and mothers.

In the process, they helped to expand the social safety net to provide more food aid, medical benefits, housing, and job training. Tens of millions of Americans have relied on that social safety net since then, through recessions, mortgage crises, and now a global pandemic. Seen in the political light cast by the social justice movements of the twenty-first century, the story of the Clark County Welfare Rights Organization and Operation Life no longer seems a historical cameo.

In March 2021, with tens of millions reeling from the economic and physical ravages of a year of COVID-19, Congress passed, and President Joe Biden signed, a bill that began to address longstanding economic, educational, local government, and health-care needs. These problems, deepened over decades of neoliberal disinvestment in government, had become exacerbated during the pandemic and lockdown. Vermont senator Bernie Sanders, chair of the Senate Budget Committee, called the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan "the most significant legislation for working people that has been passed in decades."

In many ways, it was. The bill increased access to health care by lowering the cost for millions. It raised the income limit for federal subsidies for Af- fordable Care Act coverage and dramatically increased funding for Community Health Centers—a War on Poverty innovation. ARP also expanded unemployment insurance, provided housing assistance for tens of millions facing eviction, restored funding for food stamps, and expanded the Women, Infants, and Children nutrition program.

In the summer of 2021, House Democrats pushed through a bipartisan infrastructure bill that promised to create millions of union jobs and in the fall of 2022 passed a bill that offered unprecedented levels of funding to fight climate change. Biden's Build Back Better "human infrastructure" proposals funded vast expansions in affordable medical care (added dental and vision care) and strengthened federal education and child-care programs, home health care for the elderly, and Social Security.

These bills were scuttled by Republicans and two conservative Democrats, but parts of them passed the Senate and were signed into law later in the fall of 2022. And Democrats promised to keep pushing for new social spending if they hold onto their majority in the second half of Biden's term. After decades during which politicians systematically cut federal aid to the poor, such spending would be transformative.

But none of these bills promises to trust poor people to make their own decisions in the struggle against poverty. This is something that we know can work and work well—because, in Las Vegas, Nevada, half a century ago, it did. Working people have been organizing more forcefully than we have seen in a generation. In 2021, workers in low-wage jobs across the country—in grocery stores and fast-food restaurants, in nursing homes and big box stores—have even been quitting en masse to protest the lack of paid sick leave and wages too low to live on.

Not coincidentally, wages are rising more quickly and more significantly than they have in forty years. In the summer of 2021, for the first time, the average wage of restaurant and grocery store workers passed $15 an hour. We may also soon see living wages for teachers and childcare workers in addition to universal free pre-K and free community college for all.

Most of the women of Operation Life have now passed on. But they would be happy to see this new era of activism. Still, there is one aspect of their movement that perhaps could be highlighted more dramatically. They insisted that poor mothers are the real experts on poverty, that their vision and their labor are crucial if we really hope to improve the lives of this country's poor mothers and children. "We can do it and do it better," they often said. This is a history of extraordinary women who did exactly that. We have never needed their vision more.

__________________________________

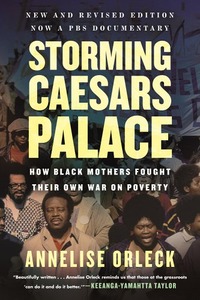

From Storming Caesars Palace Revised & Updated: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty. Used with the permission of the publisher, Beacon Press. Copyright © 2023 by Annelise Orleck.

No comments:

Post a Comment