January 20, 2021

Every little girl is unhappy in her own way and I was too, deeply so. Maybe it was because my only brother got married and left us, all of a sudden, when I was just six years old; or because of my rather old-fashioned mother, or maybe that vein of rustic cruelty in my girlfriends at the time was to blame—one day you're in; the next you're out.

Since the day I opened the bookshop, Libreria Sopra la Penna, I've barely had a conversation where I wasn't asked, "How did you get the idea to open a bookshop in a village of one hundred and eighty souls, in the middle of nowhere?"

I've spent the day wrapping. A lady from Salerno chose to celebrate Valentine's Day like this: she got a book of poems by Emily Dickinson, an Emily Dickinson–themed calendar, and a fragrance with osmanthus base notes, also named Emily, for one of her daughters. For her other girl she got a different book by Emily Dickinson, the Emily Dickinson calendar again, and a bracelet made with rose and gypsophila petals. And on top of that she bought her beloved Emily's Herbarium and another calendar too, as a treat for herself.

How did I get the idea? Ideas don't just spring out of nothing—they smolder, ferment, crowd our mind while we sleep. Ideas walk on their own two legs, follow their own parallel path in a part of us we have absolutely no idea existed, until one day they come knocking: Here we are, they say, now listen carefully! The idea for the bookshop must have been lying in wait, ensconced in the folds of that dark and joyous country we call childhood.

I came back to my village, to see if the snake had left, and if that little girl asleep under the tree hadn't been Alice in Wonderland all along.

I used to spend every afternoon at the home of my grandfather, who had one of those new radios with a cassette player—he wasn't that modern, mind you, Grandpa Tullio, but my aunts were. Modern and loose (or so said people in the village). I was a bit ashamed of that, but I adored them. At the opposite end of the spectrum sat Auntie Polda, my mother's sister, a bighearted farmer who, among other quirks, had never married and was proud of it. I spent days unbuttoning and re-buttoning her cardigans, just an excuse to sit on her lap really, and listen to her stories.

And then there was my auntie Feny (Fenysia), who was a governess. Petite and strong, shy and wise, it was she who introduced me to reading, who brought me novels given to her by the rich families she worked for. The School of Languages and Culture, which I founded a few years ago with my partner, Pierpaolo, is named after her: nurturing knowledge felt as essential as making a good minestrone (just like Auntie Fenysia's).

My mother's stories, by contrast, were the stuff of nightmares. Her favorite was the tale of a little girl who fell asleep under a tree while her mother worked in the fields, and the big fat snake who saw her and slithered down her throat. Thankfully, I can't remember how the story ends, but it's safe to say my bruised subconscious would truly heal only much later, after twelve years of work with my therapist, Lucia.

Our village was small, and I adored it: I would draw the mountain opposite our house as if it were Kilimanjaro, in spring, summer, autumn, and winter. A philosopher might say that "elsewhere" is simply any place you've never been, and to this day I have yet to set foot on that mountain. I loved the fields covered in frost—they looked made of crystal to me, like something out of a fairy tale. And I loved ants, their endless struggle to stay alive. Because if you grow up in a house without central heating, without a bathroom, and your eyes, hands, and even your ears constantly play tricks on you, it's only normal to think you might die.

My father is missing from this neat family picture—and I did miss him a lot. When he'd sit next to my bed (which I often pictured being my deathbed), my eyes, hands, and ears would settle and the world was not such a horrible place anymore.

*

I happened to start this diary on January 20, the same date that features at the beginning of Georg Büchner's Lenz. Dates matter, and we all have our January 20, the day Lenz sets off and leaves everything behind. On January 20, 1943, my mother's first husband also set off—orders had just come in, for him and the other surviving men in the Alpini brigade, to abandon the front on the Don River and retreat. It was the tragic ending to Italy's military campaign against Russia, an ending that claimed 151,000 lives, either confirmed dead or missing in action.

It was −40ºC and many of those men didn't even have shoes. Iole, my mother, was twenty-four; her husband, Marino, twenty-eight; my brother, Giuliano, six months old. The family that never was ceased to exist near Voronezh, where the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam moved with his wife before being sent to a concentration camp in Siberia, where he died. My mother waited, but no news came of Marino, as if he'd been swallowed by the steppe. Official entries on the war register end on January 23, 1943—after that, nothing. What did come was a war pension for the wives of all the missing soldiers.

Eventually, I would leave everything behind too: the most beautiful city in the world, a prestigious job, a comfortable flat near the National Library. I came back to my village, to see if the snake had left, and if that little girl asleep under the tree hadn't been Alice in Wonderland all along.

Today's orders: The Adversary by Emmanuel Carrère, Lives of Girls and Women by Alice Munro, A Boy's Own Story by Edmund White, Leaving Home by Anita Brookner, Between the Acts by Virginia Woolf, Hotel Silence by Auður Ava Ólafsdóttir.

*

January 21, 2021

The idea to open the bookshop knocked on my door one night, oven-ready. It was March 30, 2019. I had the space: there was a hill by the house where my mother used to grow lettuce and where I'd hang clothes to dry on a wire tied to two old poles. What I didn't have was the money: opening a bookshop is expensive. I had to come up with something.

When I was little, we had a huge attic. Our house was a reflection of our family—half home, half black hole. As you walked in you'd see the kitchen, then to the right a large room that my mother had partitioned using a green curtain with large pink ribbons (on the side that housed, depending on the day, either my bedroom or my deathbed), and to the left a small living room furnished in classic seventies style with table, chairs, and cupboards all made of chipboard, so shiny they looked even faker than they really were. Then there were two doors. One led to the basement, a place which alone was responsible for a good two extra years of therapy; the other door led to the attic.

There was something about the attic that made it unique. The first flight of stairs was made of perforated bricks (a job my father had started when we moved into the house), but then, as you turned a corner, the new steps ended and the original wooden staircase, which must have been a few centuries old, began. My father's love had run out. Every time I went up there, I prayed that the wooden steps would hold, that I wouldn't fall into the abyss where my old acquaintance the snake was surely waiting for me.

I got the idea so a mother from Salerno could gift her daughters two boxes full of Emily Dickinson.

On that makeshift staircase, all that was left of my father's short-lived project, my dreams began. Because once I'd turned that corner, braved the five infernal rickety steps, and reached the attic, I was safe. I'd made it. I was in my kingdom. I would set up an imaginary classroom, each child with their notebook. I played the teacher and marked my own homework from a few years before.

Or I'd read my own personal bible—the Conoscere children's encyclopedia published by Fabbri Editore, twelve volumes and four appendices. I think even my style preferences originated there—three pages were dedicated entirely to ancient Roman footwear, with which I was positively obsessed. I even bought two pairs of gladiator sandals—one golden, one snow-white—with laces that crisscrossed all the way up to the knee. I was about twelve, the same age as Lolita. Aside from that, the encyclopedia covered very serious topics:

The Italian independence movement

Saint Francis of Assisi

From wood to paper

Rome conquers Taranto

Giuseppe Mazzini

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

The tonsils

A genius named Leonardo Dante

The Five Days of Milan

Textile plants

Japan

Knowing, for instance, that female Italian revolutionaries were referred to in their secret code as "our cousins the gardeners" made me so unbelievably happy. It was like having a time machine, and opening a page at random was like pressing the "go" button. I was away, elsewhere: my favorite place. "We never test her; we're too scared," my primary school teachers allegedly told my mother, who for her part had abandoned the tale of the sleeping girl and the snake in favor of a wide range of expletives. My father, meanwhile, had left.

I'm almost done wrapping the gifts for the lady from Salerno and her two daughters. That's how I got the idea to open a bookshop in a village in northern Tuscany, on top of a hill, overlooking the Apuan Alps. I got the idea so a mother from Salerno could gift her daughters two boxes full of Emily Dickinson.

__________________________________

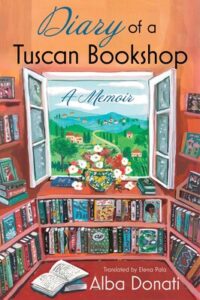

Excerpted from Diary of a Tuscan Bookshop: A Memoir by Alba Donati. Copyright © 2022 by Alba Donati. English language translation copyright © 2022 by Elena Pala. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

No comments:

Post a Comment