Writers know that every book has its own unique challenges. Sometimes a book has point of view issues. Or the timeline is tangled. Or the character's motivation evaporates and you're locked in a psychotic staring contest with your own delusion. When I sat down to write my latest thriller featuring an atmospheric physicist, the challenge was obvious: I didn't know anything about physics.

I've always been a glutton for education. I have two bachelors and a master's degree, and my book research is pure joy, whether I'm trekking through the Boundary Waters or learning the properties of rigor mortis. But the idea of tackling physics, even tangentially, intimidated me. Physics was the only class I took pass/fail in high school. I was never top of my class, but As and Bs were the norm and the idea of taking a class pass/fail, where you didn't receive a grade at the end but only had to scrape by with something more than 60%, felt like flagrant cheating. I did it anyway because, to fifteen-year-old me, physics was elusive. I understood the world in terms of marching band and Methodism. Studying the science of matter and energy felt like ignoring the actors of the play to examine the joists of the set. Teenage me was not into joists.

Three decades later, things have shifted. Forty-four-year-old me is tired of the drama. I don't know any of the actors' names and the costumes seem like recycled outfits from my teenage closet. (I made the high-waisted light wash jeans mistake once and I won't be doing it again. Also low rise, if they're coming next, can fuck right off.) Now the joists beckon. I started reading popular science books by Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking, cautiously curious about how the world around me actually works. Making the decision to writing a physicist character, while still intimidating to this pass/fail author, gave me the excuse to learn even more. Authors such as Michio Kaku, Carlo Rovelli, and Neil DeGrasse Tyson have given me a rudimentary understanding of the underlying support structures of the universe. For the following butchering of their theories and explanations, I am truly sorry. This is what happens when a murder writer swerves out of her lane.

Physics has always been a game of Russian dolls, a continual unmasking of the foundations of our reality to find something even more fundamental inside them. Aristotle believed the universe to be composed of Earth, Fire, Water, and Air, and he couldn't throw shade fast enough at Democritus of Abdera, who developed the idea of "atomos," the indivisible building blocks of all matter. Aristotle, via the later endorsement of the Catholic church, won the argument for over a millennium. Earth, Wind & Fire, baby. It was a certified Boogie Wonderland. The tides didn't turn back toward atomic theory until experiments in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. By the 17th century, Isaac Newton stepped up to the scientific stage to endorse Team Democritus and generations of Newtonian scientists made atomic theory canon.

Physics has always been a game of Russian dolls, a continual unmasking of the foundations of our reality.

One guy who definitely didn't take physics pass/fail was J. J. Thomson. The son of a bookseller, he was a quiet man who liked to garden and was famously clumsy in the lab. He also invented the mass spectrometer, discovered the electron, and cracked open the subatomic world (no big deal). Thomson discovered that not only were atoms penetrable, but they consisted mostly of empty space. Rumor had it he was afraid to get out of bed the morning after his discovery. All the comforting bricks that built his world had turned into bubbles, and he was scared that if he stepped out of bed he might fall straight through the floor.

Thomson won the Nobel Prize in 1906 for discovering electrons and subatomic particles. Thirty years later, his son won the Nobel Prize for discovering that those particles were more like waves. So which is it, you ask. Particles or waves? Yes. The answer is yes. Welcome to quantum mechanics.

The technology developed from quantum mechanics gave us the world we know today—lasers, MRIs, cell phones, Bridgerton. In the physics of the subatomic world, probability replaces certainty. (Can Bridgerton season three top the Kanthony enemies-to-lovers storyline of season two? It's entirely a game of chance.) The uncertainty of quantum mechanics blew everyone's mind, Einstein included, because it contradicted everything we thought we knew. In crime fiction, we call that a twist.

And the twists keep coming. Carlo Rovelli, the Italian theoretical physicist, is one of the people rewriting our backstory. Remember the beginning of the universe and that single point of super dense matter that went bang? Rovelli explained in Seven Brief Lessons on Physics—honestly, the longest physics class this writer's brain can handle—our origin story could have been the result of a previous collapsing universe. Instead of a big bang, it may have been the big bounce. The current expansion of the universe might just be one long exhale in a cycle of expansion and contraction, the ultimate recycling program. It could be the secret that hides all around us—in the ocean tides, the endless rise and fall of jean waistlines, the breath whispering inside our own chests.

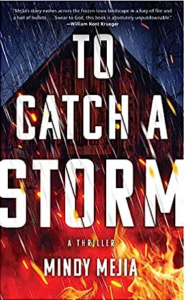

To write Dr. Eve Roth, the atmospheric physicist in To Catch a Storm, I read books and took Masterclasses and listened to podcasts and I probably understood a tenth of it, but here's what I learned: the universe is an unreliable narrator. It presents itself as a noun when it is fundamentally a verb. What appears to be a curio cabinet of fantastic objects suspended in darkness—planets, stars, and galaxies—is actually a network of vibrations and interactions where time curves and particles jump in and out of reality like this is all some spontaneous playground game. The universe does not exist. It happens.

And we happen. Humans, minute pulses within the grand symphony, mark our beats with brief and breathless insistence. We are desperate to be heard, to mean something, to be part of a whole we can feel but cannot fathom. We beat in a spectrum of ways, from the sublime to the horrific, while always gaslit by the universe's story that what surrounds us is solid and stable. That we won't fall straight through the floor.

We write stories with happy endings, with killers caught and a modicum of justice restored, and part of us recognizes the truth behind the fiction—we have to create our own certainties in a universe that offers none. In the end, I guess I didn't learn much about physics. I learned how to tell a story from the first and greatest storyteller of all.

_____________________

To Catch a Storm by Mindy Mejia is available from Atlantic Monthly Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

No comments:

Post a Comment