In March 1989, I found myself riding an elevator, heart knocking, to the fourteenth floor of the Essex House on Central Park South to interview Miles Davis. It was an assignment I'd lucked into through my magazine‑editor brother, who knew a Vanity Fair editor who'd said he needed a profile of Miles to accompany an excerpt from the trumpet legend's forthcoming memoir, coauthored by Quincy Troupe. The writer, the Vanity Fair editor told my brother, should know jazz. My brother, Peter W. Kaplan, told him that I didn't just know jazz; I knew everything there was to know about it.

This was hyperbolic, to put it mildly. I liked jazz—liked it a lot, what little I knew of it. My record collection, just beginning to shift from LPs to CDs, was primarily rock and blues, with a bit of classical and a smattering of jazz. I was in the process of educating my ears—still am—but it was and is a long, slow process. I knew Miles Davis was a titan in his field; I knew he'd played with Charlie Parker in the 1940s. That was about it. I owned exactly two Miles albums: 1969's Filles de Kilimanjaro, which I'd bought simply because I heard it in a friend's dorm room and it was quietly beautiful, and the dark and menacing 1970 Bitches Brew, which I'd bought because, when it was issued, buying it felt vaguely compulsory.

His status as a personage, an icon, had always vied with his stature as a musician.

When I complained to my brother that I was very far from knowing all there was to know about jazz, he stopped me. This was Vanity Fair, he said, with some italicized heat.

I took his meaning. The magazine, then under the leadership of legend‑under‑construction Tina Brown, was the magazine to write for in those days. And I had a wife and an infant son and a mortgage in Westchester, and a chance to get in the door at Vanity Fair would be a plum. One heard they were issuing fat contracts to writers they liked.

I called my brother's editor acquaintance there, and, after surprisingly little discussion of my putative jazz expertise, got the assignment. I promptly went to Tower Records and bought every Miles Davis CD they had, not thinking about when I might have time to actually listen to all of them. Then I phoned Miles's publicist and proudly announced myself as The Writer from Vanity Fair.

It was only on that elevator at the Essex House, with the publicist by my side, that the full weight of my fraudulence began to sink in on me. I was nobody! I knew nothing! No Google then, no Wikipedia; no facile way to pose as an instant authority. I'd leafed through the advance copy of Miles's memoir that the publisher had sent me, intimidated by its heft, not to mention its general tone of darkness and anger, not to mention the masses of jazz names I knew little or nothing about.

I'd written up a too short and shallow list of questions for him, naïvely hoping that once a flow of conversation was established, further thoughts would occur to me. In my backpack I had my Soviet‑style Radio Shack cassette recorder, the size and weight of a dense college textbook (it ran on five C batteries). I also had extra batteries and a half dozen blank cassettes. The backpack was heavy. The publicist had promised me one meeting of one hour, no more. How could I possibly get all I needed in an hour? And what did I need, anyway?

I often think of the line attributed, in various forms, to Mike Tyson: Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth. Every interview is a kind of punch in the mouth. You walk in with certain expectations about the person you're about to talk to, and bang, the person is inevitably somebody different from the person you expected, and everything you'd anticipated evaporates. Wise interviewers learn to roll with the punches, to bob and weave and temporize on the spur of the moment. I was anything but wise in those days. In addition, I was thoroughly pre‑intimidated by the time we arrived and Miles Davis opened his apartment door, a small but startling presence: dark eyes glittering, naked to the waist, wearing black pajama pants and what looked like an extravagant wig of brown curls.

We settled down to talk. "Now," he said. "What you want to know?" What did I know? Nothing. What did I want to know? Everything.

*

But Miles Davis wasn't about to tell me everything. He couldn't tell me one percent of one percent of everything in our allotted hour—though the one hour turned into almost two, at the end of which I asked timorously if I might have some more time, and Miles rasped, "Come back tomorrow."

Of course I returned the next day, without the publicist this time, and the second session went much like the first, full of Miles's sentence fragments about tangential topics; further discussion about his artwork; stories about matters and people I hadn't the wherewithal to understand; and minimalist, wandering answers to my jazz questions. At the time I had the sinking feeling that I would draw little of substance from him, even over the course of three hours, certainly not enough to make a piece that would satisfy what I imagined were the Olympian standards of Vanity Fair.

But the musical standards of Vanity Fair in 1989 were far from Olympian. Music was scarcely the point. What the magazine was interested in was celebrity, and style and buzz and dirt, and with Miles and his frequently scabrous memoir, Vanity Fair had all of this in abundance. His status as a personage, an icon, had always vied with his stature as a musician. That was the way he wanted it; that was the way he designed it: from the moment he dropped out of Juilliard and joined Charlie Parker's band in 1945, he was an energetic shaper of his own image.

He was a visual as well as a sonic phenomenon. He had a lot to work with. He was beautiful and dark, literally and figuratively; he was angry, tempestuous, and always stylish, whether in the Ivy League-bespoke look he favored in the fifties and early sixties or the outer‑space outfits of the mid‑ to late eighties. He was a Black man who lacked any hint of the ingratiation that the white world preferred (or demanded) from its Negro entertainers, and that the entertainers sometimes, doubtless with irony or fury in their hearts, supplied. He wore shades onstage. He didn't announce tunes—he didn't speak at all. He famously turned his back to his audiences, both while playing and laying out.

This was Miles Davis the celebrity. The question of Miles the musician in 1989 was a more complicated matter. From the beginning, his musical life had been a series of restless moltings: of collaborators, of styles, of lovers and friends. From Juilliard to Bird to The Birth of the Cool to the Blue Note and Prestige albums to a free fall into the hell of heroin addiction to getting clean and coming back triumphantly in Newport in 1955 to signing with Columbia, the Rolls‑Royce of record labels, to the first great quintet (Miles, John Coltrane, Paul Chambers, Red Garland, Philly Joe Jones) to replacing Garland with Bill Evans, to losing Evans, then bringing him back for Kind of Blue...

After Kind of Blue Davis would continue to evolve incessantly, initially with that album's sextet—minus Evans, who'd left to lead a trio of his own, and would maintain that format for the remainder of his career, and then without Coltrane, who became a leader and an artistic trailblazer in his own right. Then, in the early sixties, Miles formed a second great quintet, including saxophonist Wayne Shorter, pianist Herbie Hancock, drummer Tony Williams, and bassist Ron Carter.

And then, in the late sixties, he abandoned acoustic jazz altogether, moving to the easy/uneasy blend of jazz and rock that would cause consternation among jazz purists and come to be known as fusion. Then, in 1975, plagued by profuse health problems and addictions, he left music altogether, not to return until 1981. Audiences and record buyers welcomed his comeback, though jazz's zealous gatekeepers continued to fret about his stylistic excursions and commercial aspirations.

Ever since Bitches Brew, jazz purists had been decrying what looked like naked commercialism on Miles's part: many knives were sharpened for his every move. His 1985 Columbia album You're Under Arrest contained, besides several original compositions, covers of two huge pop hits, Cyndi Lauper and Rob Hyman's "Time After Time" and John Bettis and Steve Porcaro's "Human Nature," from Michael Jackson's mega‑selling album Thriller. Rolling Stone's decidedly mixed review of You're Under Arrest spoke of the CD's "instant notoriety" in jazz circles.

It didn't help matters that Miles was inevitably compared with his "anointed heir and label mate, Wynton Marsalis." Marsalis, a mere twenty‑three but already world famous when You're Under Arrest was released, was the purist‑in‑chief. A startlingly gifted trumpeter from a brilliant New Orleans jazz family, he first came on the scene in the late 1970s and immediately began making a splash, both with his playing—not only of jazz but also the classical trumpet repertoire—and his outspoken critiques of the contemporary jazz scene, most pointedly of his former idol, Miles Davis.

The young trumpeter was highly opinionated and highly quotable, and from the beginning the music press, sniffing a possible feud, gave Marsalis's venting about Miles—he even critiqued the outlandish outfits Miles had taken to wearing onstage, calling them "dresses"—plenty of column inches. The first time the two met, Miles said, "So here's the police."

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, George Butler, the vice president for jazz A&R (artists and repertoire) of Davis and Marsalis's mutual record label, Columbia, tried vigorously to get Davis to bestow his blessing on the up‑and‑comer, to little avail.

"George [kept] trying to make friends out of [me and] Wynton Marsalis," Miles told me. "Like, I'd be sketching, right? And the phone would ring. Cicely [Tyson] says, 'It's George.'

"So I said, 'What does he want? Can he tell you?' She said no. So I answer the phone. Say, 'George, what it is?'

"He says, 'Why don't you call Wynton up?' "I say, 'For what?'

"He says, 'Because it's his birthday. He's in St. Louis.' "I say, 'Oh, George—' "

I laughed.

"See, you laughing," Miles said. "But when that shit comes at you like that, you're like, What? And Wynton and I get together and talk about music; he tells me he's tired of playing classical. I said, 'But you're the only one playing it. Of our race. And you play it good.' "

This is what Miles said he said to Marsalis. But in various public contexts he'd also potshotted right back, often asserting what he'd said after Marsalis recorded his first baroque concerto album in 1982 (and would repeat for posterity in his autobiography): "They got Wynton playing some old dead European music."

And in June of 1986 there had been an incident.

*

The episode, at the first Vancouver Jazz Festival, was the most exciting thing that had happened in jazz for years, throwing a spotlight on a genre that, in American culture at large, had long since contracted into niche status. The event quickly took on folkloric dimensions. In some accounts, there had even been a threat of physical violence between the frail sixty‑year‑old Davis and the twenty‑four‑year‑old Marsalis. In Wynton's 2015 retelling, it all started with the goading of the three musicians who played with him at the festival—the drummer Jeff "Tain" Watts, the bassist Robert Hurst, and the pianist Marcus Roberts.

It didn't help matters that Miles was inevitably compared with his "anointed heir and label mate, Wynton Marsalis."

The four were in a car approaching Vancouver, Marsalis recalled, when Roberts, Watts, and Hurst began teasing him about some belittling remarks Miles had made to the press about Wynton and his musical family, New Orleans jazz royalty (his father, Ellis Marsalis Jr., and his three brothers, Branford, Delfeayo, and Jason, were all renowned jazz musicians). How long was Wynton going to stand for this? they asked, jokingly. Was he scared of little old Miles? Davis was going to play that night, they pointed out, and they were off. Why not jump onstage with your horn, barge in on his act?

When Wynton replied, seriously, that he had too much respect for Miles to do that, the others began laughing at him and playfully betting that he was too scared to face off with the great man. Marsalis laughed along with them as they raised the ante. When the bet reached $100 apiece, and Wynton saw that his bandmates were serious, he said he would do it. And so he did.

According to a wire‑service report,

Wynton Marsalis surprised everyone—especially Miles Davis—when he walked onstage with his horn, uninvited and unannounced, as Davis and band were in the midst of a blues number. The upstart Marsalis approached the veteran Davis but Miles shook his head in a negative fashion. Instead of leaving, Marsalis walked to a microphone and began playing, which resulted in Davis stopping the music. The abashed Marsalis, who has always revered Davis, then walked off. "I don't know why he was up there," Miles said. "We have things that we do and we time everything. If he wants to jam, why doesn't he go out to a club? I wonder what would happen if I did that?"

As Miles recalled the incident in his autobiography, he and his band were playing to a standing‑room‑only crowd at an outdoor amphitheater. Engrossed in his music, he suddenly sensed a presence in his periphery, and saw the audience reacting strongly—and then Marsalis was standing right next to him and whispering in his ear, "They told me to come up here." Miles was furious. "Get the fuck off the stage," he said. Marsalis looked shocked. "Man, what the fuck are you doing up here on stage?" Davis said.

"Get the fuck off the stage!"

Miles stopped the band, he writes, because Marsalis "wouldn't have fit in. Wynton can't play the kind of shit we were playing."

Marsalis claimed that Davis was playing the organ when he walked onto the bandstand, and that the music was too loud for him to hear anything Miles said. Once the band stopped, Wynton recalled, Miles said a few words to him, but "fuck" wasn't one of them. And even though Davis was physically fragile, Marsalis, remembering that the great trumpeter had once trained as a boxer, watched his hands carefully, certain that any kind of physical altercation would go in his, Wynton's, favor, and wind up making him look like nothing but a bully.

The story, Marsalis said, blew up out of all proportion to what had really happened or what he and his band ever thought it would be. And, he said, he never collected his $300.

One more recollection should be heard: that of the trumpeter Wallace Roney, Miles's friend and only certified protégé, who played at the festival in the drummer Tony Williams's group and was in the audience that night. "Wynton walked onstage—Miles had just taken a solo," Roney told me. "And Wynton went up and said, 'Can I sit in?' And Miles said, 'What?' First of all, his back was to him—Wynton said, 'I would like to sit in, and anytime you want to sit in with my band, you can.' [Miles said] 'No. No. Get off the stage.' And Wynton didn't get off the stage, and Wynton just waited, and he took a solo. You should hear it. You'll hear a big difference between Miles and Wynton, by the way. And then after one chorus of the blues, Miles cuts it off. And the people boo Miles. Miles says, 'Get off my fucking stage, motherfucker.' That's what he said. And Wynton says, back to him, 'Fuck you.' And walks off the stage.

"Now Wynton talks about, he didn't want to do it, and his band [made him do it]—you know, it's bullshit."

The truth may be a combination of all accounts, but let it not be forgotten that ambushing a musician—jumping up on stage in the middle of his set and trying to outplay, or "cut," him—is an ancient and semi‑honorable tradition in jazz, one that Miles himself had engaged in as a young man, and certainly one that Wynton Marsalis, the ultimate traditionalist, knew all about.

__________________________________

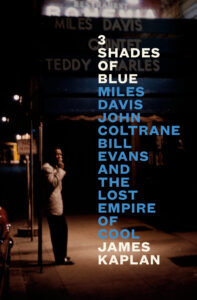

From 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool by James Kaplan. Used with the permission of the publisher, Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2024 by James Kaplan.

No comments:

Post a Comment